What is Seismology?

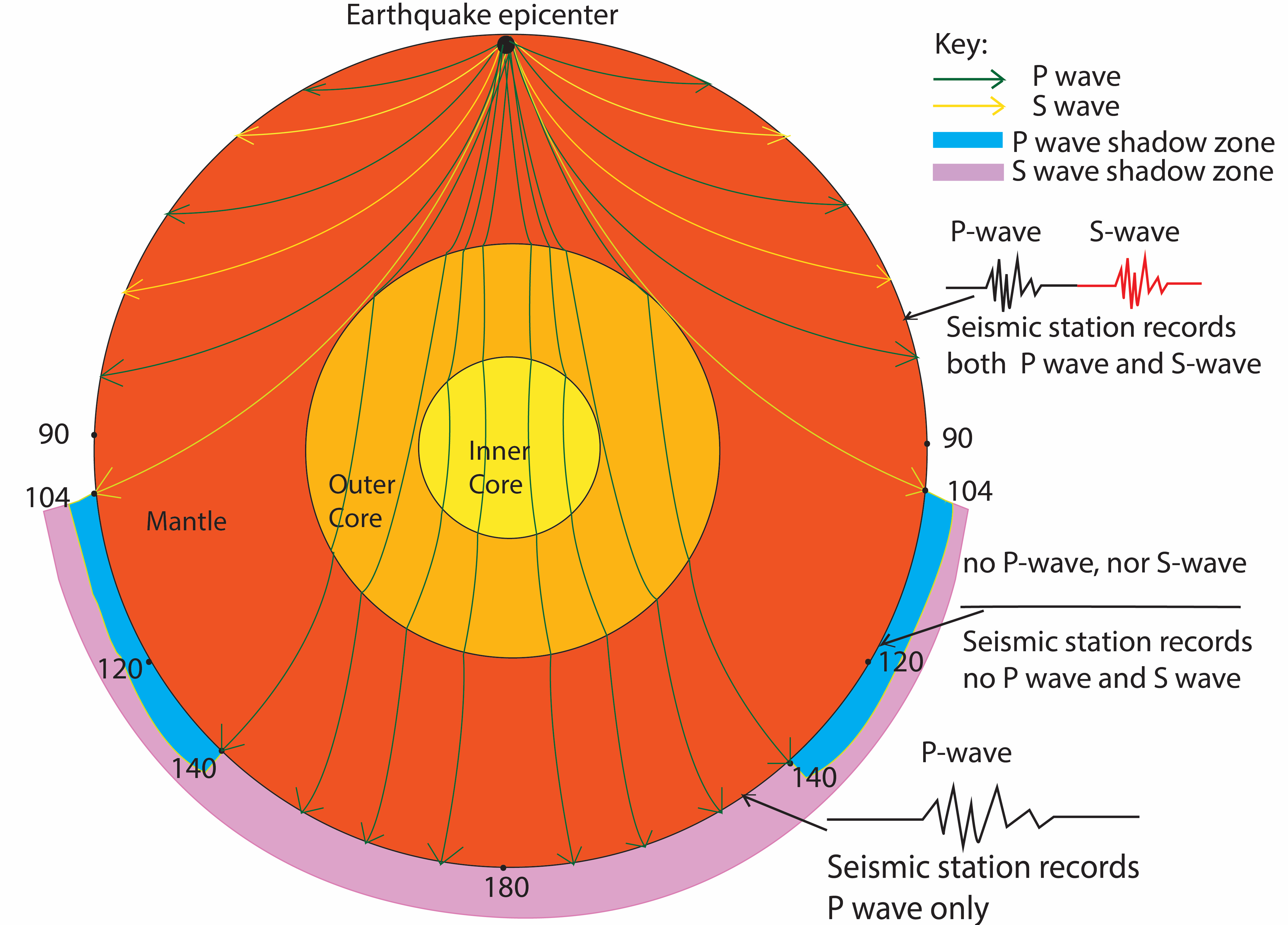

Figure 1: The radial structure of the earth and ray paths of P and S-waves though the earth. Due refraction of seismic waves at core-mantle and inner-outer core boundary, seismic stations at different distance from the epicentre record different signals that correspond to the radial structure of the earth.

Table of Contents

- Early studies of earthquakes

- The birth of seismograph and wave theory

- The interpretation of seismograph and radial structure of the earth

- Other application of seismology

- Plate tectonics and Seismology

- Modern Seismology

- Reference

Early studies of earthquakes:

The history of seismology can be traced back to 300BC when Aristotle suggested that earthquakes were caused by subterranean winds collision. The invention of seismoscope by the Chinese astronomer Chang Heng at 132BC (Dewey & Byerly, 1969) enabled earthquakes documentation and catalogue in China and Japan respectively. The expansion and professionalizing of science in 19th century promoted the study of earthquakes. The earliest attempted was to quantify the intensity of earthquakes (Agnew, 2002). Italian volcanologists Giuseppe Mercalli created Mercalli intensity scales that describe the felt effects of large earthquakes. In the 1800s, scientists like Cauchy, Poisson, Stoke and Rayleigh developed the elastic wave propagation theory in which they described the main waves types that travel through solid materials (Shearer, 2009). The waves are classified into body and surface waves. Body waves travel through the bulk earth and consist of longitudinal (e.g. primary (P) waves) and transverse waves (e.g. secondary (S) waves). S-waves cannot travel through liquid. Surface waves travel along the free surface. Rayleigh waves and Love waves are surface waves. Early seismologists W. Hopkins and R. Mallet applied these results to earthquake studies. W. Hopkin demonstrated the wave arrival time can be used to locate earthquakes. R. Mallet constructed the first map that illustrated the seismic and aseismic regions of the world (Agnew, 2002). He also attempted to infer the hypocentre of the earthquake from the direction of wave arrivals.

The birth of seismograph and wave theory:

The first seismograph was built by Filippo Cecchi in 1875 (Dewey & Byerly, 1969). The early network was intended to detect ongoing unfelt small motions that were related to weather or earthquakes. The introduction of horizontal pendulum seismograph by British scientists J.A. Ewing and John Milne provided quantitative instrumental records that allowed studies of all aspects of earthquakes and elastic waves (Agnew, 2002). However, the undamped nature of the early equipment only allows it to detect large ground motion (Shearer, 2009). The problem was solved in 1898 when E. Wiechert introduced the first seismometer with viscous damping, such equipment can produce a record for the entire duration of an earthquake. E. Wiechert also deduced wave velocity from travel-time, which is known as Heglotz–Wiechert method (Ritter & Schweitzer, n.d.). In the early 1900s, B.B. Galitzen developed the first electromagnetic seismographs (Shearer, 2009). All modern seismographs are electromagnetic as they have extraordinary high sensitivity and accuracy.

The interpretation of seismograph and radial structure of the earth:

By 1890, It was agreed that the depths of the earth were hot and dense. Lord Kelvin and G.H. Darin’s tidal studies confirmed that a large part of the earth is solid and thus can transmit body and surface waves. The availability of seismographs led to rapid progress in the identification of earth seismic velocity structure (Shearer, 2009). In 1900, R.D. Oldham distinguished P, S-waves and surface waves by interpreting the seismograph of 1897 Assam earthquake. Later he also proposed the presence of the liquid core by recognizing P and S-wave shadow zone (shown in Figure 1). In 1907, K. Zoeppritz published the first travel-time table for P-wave, S-wave and surface waves (Ritter & Schweitzer, n.d.). Two years later in Croatia, A. Mohorovicic observed a velocity discontinuity that separates crust and mantle at depth about 50km (Shearer, 2009). In 1914 B. Gutenberg utilized the Heglotz–Wiechert method to determine the first accurate estimate of the depth of core-mantle boundary and a velocity profile that included the core phases. The structure of Earth was further refined by the discovery of the solid inner core in 1936 by Inge Lehmann from the recognition of weak P-wave arrival at P-wave shadow zone. The development of normal mode seismology in the 1960s and 1970s confirmed the presence of inner core and provided constraints on Earth structure and density (Shearer, 2009). In 1981 Dziewonski and Anderson published the Preliminary Reference Earth Model which is regarded as a valid model for Earth’s internal structure.

Other application of seismology:

The invention of seismograph allowed a quantified measure of energy released from earthquakes. In 1935, C. Richter developed a logarithmic scale of earthquake magnitude, the “Richter scale”. The body wave magnitude utilizes P-wave amplitude and the measurement is corrected with the depth and distance between the source and receiver. Surface wave magnitude utilizes Rayleigh wave amplitude. These two magnitudes are not the same but are broadly related. The difference in these two magnitude estimates is a method to distinguish between a natural earthquake and a nuclear test. In 1946, an underwater nuclear explosion led to the first detailed seismic recordings of nuclear test. The ability of seismology to detect nuclear bomb testings was soon recognized by the US military. It led to the establishment of the Worldwide Standardised Seismograph Network (WWSSN) (Hutt & Peterson, 2014). The WWSSN system consisted of three short-period seismographs, three long-period seismographs and various support equipment. This grand experiment produced an unprecedented collection of high quality, continuous data from approximately 100 stations around the world (Hutt & Peterson, 2014). By deploying a seismometer on Moon and conducting passive seismic experiments, seismologists determined the internal structure of the moon (Goins, et al., 1981).

Plate tectonics and Seismology:

Early studies of plate tectonics focused on earthquake mechanism. By relating what happened at the source to the seismograph, Japanese seismologist T. Shida (1917) showed a pattern of first motion divided into quadrants separated by nodal lines (Agnew, 2002). The more theoretical study was conducted by H. Nakano who introduced the concept of seismic radiations from a double-couple source in 1923. Five years later, K. Wadati reported the first convincing evidence for deep-focus earthquake (Shearer, 2009). Deep focus earthquakes are typically observed along Wadati-Benioff zones which correlate to subduction zones. In the 1960s, sea-floor spreading and plate tectonics theory became well established. The contribution of Seismology came from ocean seismicity and focal-mechanism study. The former showed oceanic earthquake appears to occupy only a narrow and continuous zone along the mid-ocean ridge. The later links earthquakes to specific fault types.

Modern Seismology:

In 1976, the first three-dimensional earth modeling was introduced. This new framework produced more detailed and accurate information about the earth’s interior (Aki, et al., 1977) and promoted the study of heterogeneity in the 3D structure of the earth. For example, seismology is used to resolve the structure of fault zones at depth, the deep roots of continents, the structure of ocean spreading centers, the nature of convection within the mantle and, the complicated details of core-mantle boundary and the structure of the inner core (Shearer, 2009).

References

- Agnew, D. C., 2002. International Handbook of Earthquake and Engineering Seismology. San Diego: Academic Press.

- Dewey, J. & Byerly, P., 1969. The early history of seismometry (to 1900). Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America , 59 (1), pp. 183-227..

- Goins, N. R., Dainty, A. M. & Toksöz, M. N., 1981. Lunar seismology: The internal structure of the Moon. Journal of geophysical research , 10 June , 86(B6), p. 5061–5074.

- Hutt , C. R. & Peterson, . J., 2014. World-Wide Standardized Seismograph Network: A Data Users Guide , Reston : USGS.

- Ritter, J. R. & Schweitzer , J., n.d. German national report, Part C. Biography of Angenheister and of Geiger, Weichert’s Biliography, and Biographical Notes

- Shearer, P. M., 2009. Introduction to Seismology. Second ed. New York: Cambridge University Press