The relationship between the Siberian Traps and the end- Permian mass extinction

The end-Permian mass extinction is the most severe extinction event on earth history. Dating of Araguinha crater in central Brazil and rocks from the Siberian Traps showed both events are synchronous with the mass extinction event. While the asteroid impact hypothesis remains controversial, volcanism (i.e. the Siberian Traps) is the major cause of the end-Permian mass extinction. The Siberian traps had a size of ~7,000,000 km2 and a volume of ~4,000,000 km3. It ejected at least 30,000Gt carbon (corresponds to 100,000Gt carbon dioxide) and 6300-7800Gt sulphur. This report aims to investigate how the Siberian Traps eruption affected climate and biosphere in the end-Permian, therefore the killing mechanisms and their interactions.

Table of Contents

Background

In late Permian, the biospheres were dominated by marine species, especially Palaeozoic marine faunas such as brachiopods, bryozoans and several stalk echinoderm groups like the crinoids (Erwin, 1993). Mesozoic faunas (e.g. molluscs) and Cambrian faunas (e.g. trilobites) were also present but were less significant. On land, common terrestrial planets included conifers, callipterids, and a variety of seed planet generally described as pteridosperms. Fossil records also showed diverse vertebrates and insects groups in late Permian (Erwin, 1993).

By the early Permian, the formation of the supercontinent “Pangea” was largely complete. The Caledonian orogeny involved in the formation of Pangea and the supercontinent itself had a great impact on eustatic sea level and the global climate. The sea level dropped (Fig. 3) and warm shallow marine was reduced significantly (Erwin, 1993). In terms of climate, the global temperature began to increase in the early Permian. An approximation showed that prior to end-Permian mass extinction, tropical sea surface temperature ranged from ~22 to 25 °C (Cui & Kump, 2015).

Introduction

The extinction events

The end-Permian mass extinction is the most severe extinction event identified on earth (Fig. 2). About 96% of all species and over 90% of marine species went extinct (Song et al., 2013). The U/Pb dating of closed-system zircon showed the main pulse of the extinction was 252.6 ± 0.2 Ma (Mundil et al., 2004). The marine extinction event can be considered having two phases, separated by an 180,000-year second stage appeared in Changhsingian, resulting in an elimination of 71% of the remaining species (Song et al., 2013). The second phases changed the marine ecosystem fundamentally as marked by the extinction of almost all Cambrian faunas, a decline of Palaeozoic faunas and a prosperity of Modern faunas afterwards. Because of the difference in selectivity shown by two phases, Song et al., (2013) suspected they were caused by different environmental crises.

The first stage (also known as the late Maokouan extinction) devastated many taxa (such as reef taxa and radiolarians) in warm, shallow waters and surface waters

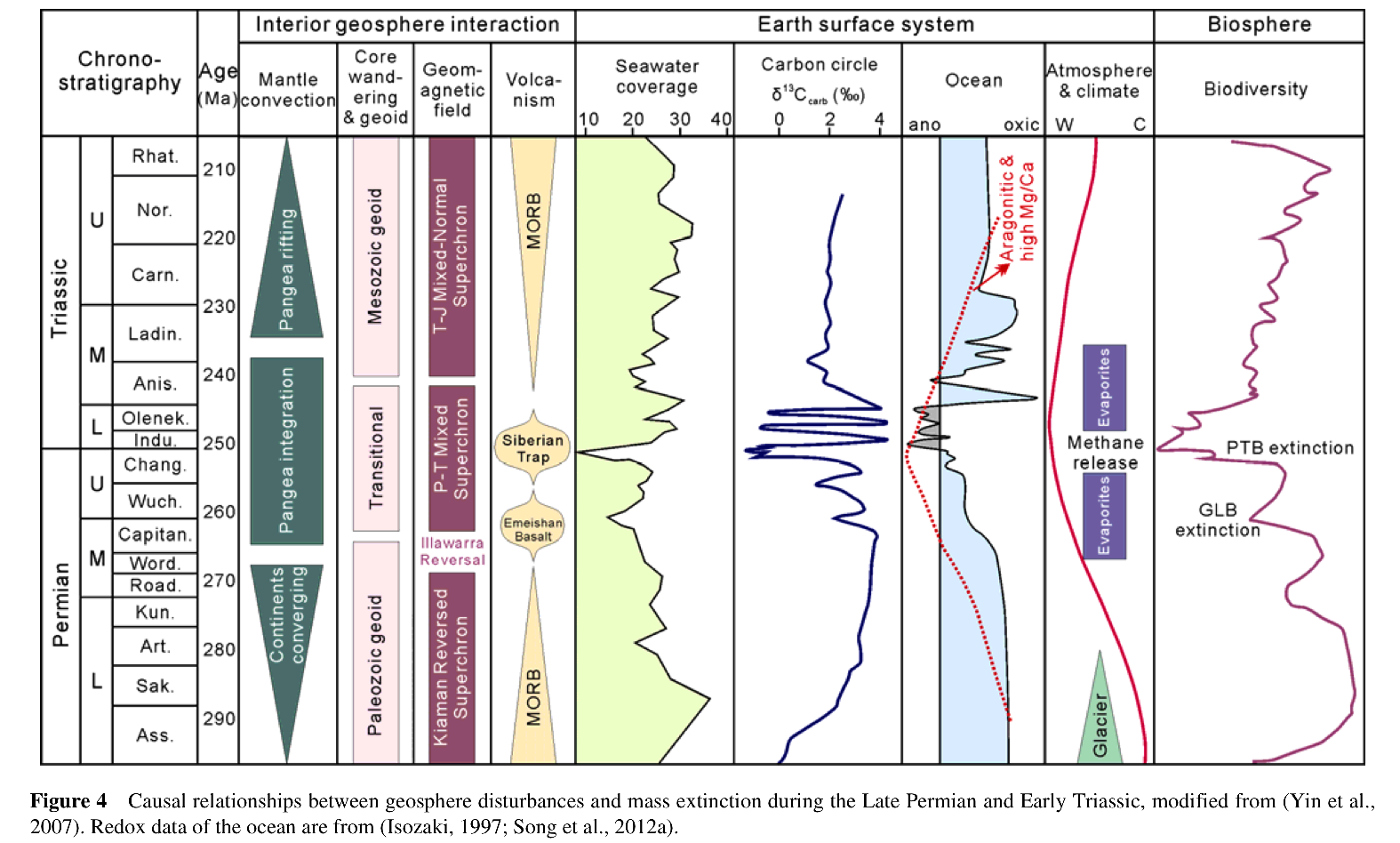

Figure 3 Relationships between geosphere disturbance and mass extinction during the end-Permian and Early Triassic. After (Yin, H. & Song H. 2013).

recovery phase (Yugan et al., 1994; Song et al., 2013). The first stage of extinction happened at around ~260Ma, causing an elimination of 57% of species, whereas the (Song et al., 2013). The study of the Maokouan-Wujiapingan boundary in South China confirmed the coincidence between Permo-Triassic boundary (PTB) volcanic

ashes and mass extinction (He et al., 2014). This study also demonstrated the volcanic ashes have no genetic link with Siberian Traps. He et al. (2014) proposed they may come from ignimbrite flare-up due to rapid subduction in the assembly of the Pangea Supercontinent. The eruption of Siberian Traps was associated with the second stage of extinction as it has a strong connection with extinction mechanisms including volcanic winter, global warming, marine anoxia and ocean acidification (Hallam & Wignall, 1997; Iacono-Marziano et al., 2012; Clarkson et al., 2015; Cui & Kump, 2015). In this report, I am going to consider the geological evidence for the mechanisms, as well as their interactions.

Siberian Traps

The Siberian Traps is one of the largest known igneous provinces. It has a size of ~7,000,000 km2 andavolumeof~4,000,000km3 (Ivanov, 2007). The eruption occurred at 250Ma and lasted no more than 2 Ma. The evidence presented by Pringle et al. (2009) indicated the volcanism continued into Triassic. The 40Ar/39Ar ages showed the main stage of volcanism partially predates and is synchronous with the end-Permian mass extinction (Pringle et al., 2009). The eruption occurred where the host rocks are rich in carbonates, sulphates, salts, and organic compounds. Therefore, as well as causing a voluminous emission of CO2, methane and sulphur aerosols, many volatiles including S, Cl and F were also injected. By measuring the chloride, fluoride and sulphur concentration in the melt inclusion from Siberian Traps, Black et al., (2012) estimated the eruption released 6300–7800 Gt S, 3400–8700 Gt Cl, and 7100–13,600 Gt F. These gases, dust and volatiles contributed to the perturbation of global environment during the end- Permian.

The Extinction Mechanism

After examined varied geological evidences for these mechanisms. I came to conclude the Siberian Traps eruption led to a series of complicated, inter-related climatic, ecological and geo-chemical factors which led to the end-Permian extinction. The main mechanism is a short- term volcanic winter followed by a long term global warming with subsequent ocean anoxia, euxinia and acidification playing a minor role. The explosive eruption ejected CO2, sulphate aerosols, dust, volatiles (e.g. Cl, F, S). The CO2 emission is associated with global warming, ocean anoxia and acidification, while sulphate aerosols and dust emission caused a short- term (3-6 months) cooling effect. The CO2 emission and methane hydrate from continental shelf and permafrost exacerbated the long-term global warming. The increase in global temperature triggered ocean anoxia. CO2 emitted was also absorbed by the ocean, reduced the pH of seawater. Ozone depletion occurred due to the volatiles emission from Siberian Traps. The increase in UV radiation aggravated damages caused by other climate changes. Ocean acidification devastated shell–forming organism while ocean anoxia eliminated benthic and deep marine taxa. In addition, volcanic winter damaged marine ecosystem in tropical- subtropical region. Reef and phytoplankton taxa were largely affected. Volcanic winter and global warming were responsible for the rapid decline in terrestrial tetrapods, gigantopterids and high latitude terrestrial floras.

FOOTNOTES

This is a short summary of my original report. If you are interested in the detaile mechanism, please get in touch

References

- Erwin, D. H., 1993. The great Paleozoic Crisis. New York(Chichester): Columbia University Press.

- Cui, Y. & Kump, L. R., 2015. Global warming and the end-Permian extinction event: Proxy and modeling perspectives. Earth-Science Reviews, October, Volume 149, p. 5–22.

- Song, H., Wignal, P. B., Tong, J. & Yin, H., 2013. Two pulses of extinction during the Permian–Triassic crisis. Nature Geoscience, Volume 6, p. 52–56.

- Mundil, R., Ludwig, K. R., Metcalfe, I. & Renne, P. R., 2004. 0 0 REPORT Age and Timing of the Permian Mass Extinctions: U/Pb Dating of Closed-System Zircons. Science, 305(5691), pp. 1760-1763.

- Yugan, J., Zhang, J. & Shang , Q., 1994. Two Phases of the End-Permian Mass Extinction. In: Pangea: Global Environments and Resources — Memoir 17, 1994. s.l.:CSPG Special Publications, pp. Pages 813-82

- Hallam, A. & Wignall, P. B., 1997. Mass extinction anf their aftermath. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Iacono-Marziano, Giada ; Marecal, Virginie ; Pirre, Michel ; Gaillard, Fabrice ; Arteta, Joaquim ; Scaillet, Bruno ; Arndt, Nicholas T., 2012. Gas emissions due to magma–sediment interactions during flood magmatism at the Siberian Traps: Gas dispersion and environmental consequences. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, Volume 357-358, p. 308– 318.

- Clarkson, M. O. et al., 2015. Ocean acidification and the Permo-Triassic mass extinction. Science, 348(6231), pp. 229- 232. 9.Black, Benjamin A. ; Lamarque, Jean- François ; Shields, Christine A. ; Elkins- Tanton, Linda T. ; Kiehl, Jeffrey T.,2013. Acid rain and ozone depletion from pulsed Siberian Traps magmatism. Geology, 42(1), pp. 67-70.