Socio-economic and environmental impacts and prospects of geothermal energy in Kenya

Kenya has more than half of its energy mix coming from renewables. Situates at the East-Africa rift valley means exploiting geothermal energy is both cost-effective and efficient

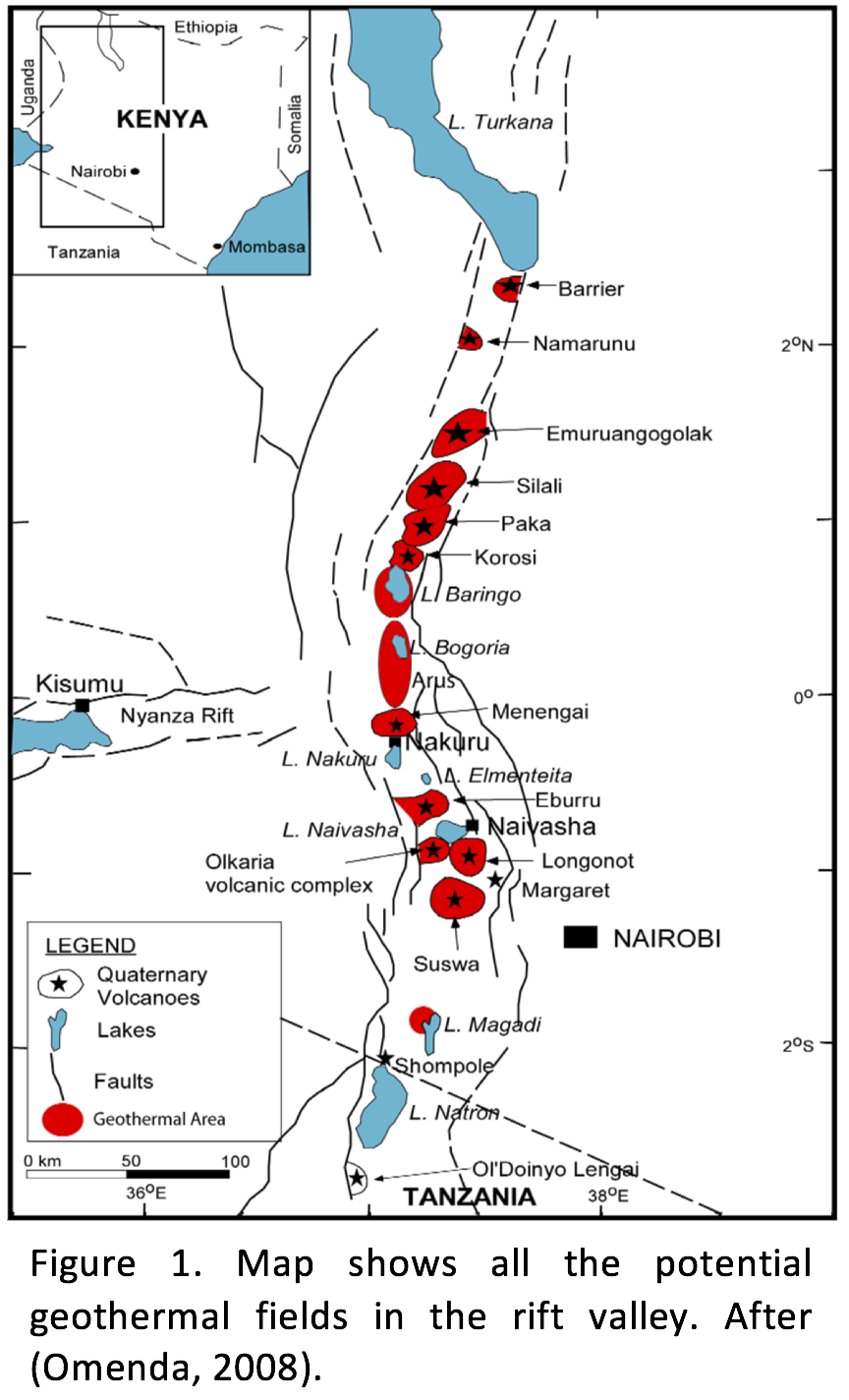

There is about \(4.3 \times 10^7\) EJ thermal energy stored down to 3km within the continental crust, which is considerably greater than the world’s total primary energy consumption (560 EJ) (World Energy Council, 2016). Geothermal energy is the heat contained within the Earth that generates geological phenomena on a planetary scale. In the exploitation, energy recharge by advection happens on the same timescale as the heart production, making geothermal a renewable energy resource (Dickson & Fanelli, 2003). The utilization of geothermal resources depends on temperatures. High-temperature geothermal resources (>150C) is used to generate electricity while medium to low-temperature resources (<150C) can be used for greenhouse heating and soil warming (Fig. 1) (Gudmundsson, 1988). Electricity generation mainly takes place in conventional steam turbines and binary plants, depending on the characteristics of the geothermal resource (Fig 1) (Dickson & Fanelli, 2003). Power stations using conventional steam turbines have a capacity up to 110MW. Binary plants usually consist of a series of small modular units of a few hundred kW to a few MW. It is a very cost-effective and reliable means of generating electricity from water-dominated geothermal fields (Entingh, et al., 1994).

Table of Contents

- The rift valley and geothermal field in Kenya

- Benefits and challenges of geothermal energy development

- Conclusion

The rift valley and geothermal field in Kenya

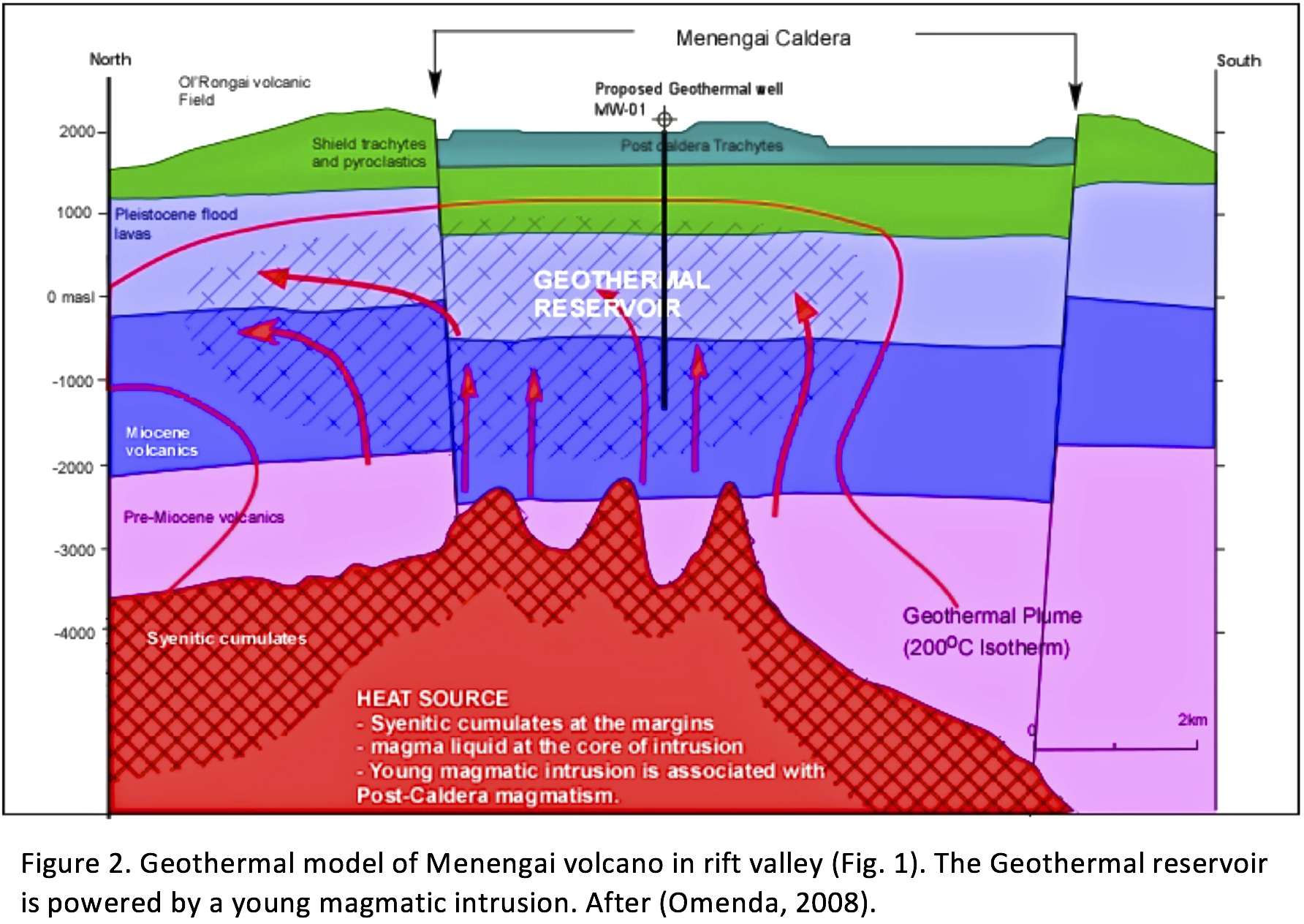

The East African Rift system runs through Kenya from north to south. It is caused by the separation of Nubian Plate and Somali plate, which may be driven by a mantle plume (Dawson, 2008). Wheildon, et al., (1994) presented evidence, demonstrating high heat flow on the rift floor, which correlates with quaternary volcanoes at the rift axis (Mwakio, 1996). The continental rifting started 23 Ma followed by basaltic, phonolitic and trachytic volcanism, extensive faulting and thinning of the lithosphere. The results have been a 50-70 km wide rift structure in central Kenya (Mwakio, 1996). Geothermal reservoirs in Kenya are either associated with shallow magma chamber underneath young volcanic centres (Fig. 2) or fissures that are related to rift floor fault systems. The former is the most dominant field within the Kenya rift valley (Riaroh & Okoth, 1994; Omenda, 2008).

Development of geothermal energy in Kenya:

Geothermal is the major energy source in Kenya which contributes 26% of the country’s electricity generation (Republic of Kenya, Ministry of energy and petroleum , 2016; Mwakio, 1996). The exploration of geothermal reservoir started in the 1960s with surface exploration involving two geothermal holes drilled at Olkaria (Fig. 3). From the 1970s, more geological and geophysical surveys were carried out. With funds from the United Nation Development Programme (UNDP), deep exploration wells were commenced, resulting in the confirmation of electricity generation potential (Omenda, 2008). The first generating unit was commissioned in 1981, followed by the second and the third units in 1982 and 1985 respectively (KenGen, n.d.). These three units formed the Olkaria I power station which is the first geothermal plant in Africa and has a power output of 45 MW ( KenGen , 2017; Omenda, 2008). In 2010 and 2014, 105 MW Olkaria II power station and 280MW Olkaria IV power station were built respectively (KenGen, 2017). There are constant explorations and studies of geothermal reservoirs across the rift valley in Kenya, such sites include Longonot, Eburru and Lake Bogoria (Fig. 3) (Omenda, 2008; Kiplagat, et al., 2011).

Benefits and challenges of geothermal energy development:

Socio-economic impacts:

The rift valley is home to one of the Kenya’s poorest rural communities–the Maasai. The level of education is low and their main sources of livelihood are pastoralism and livestock trading. They also generate incomes from tourism and low skill employment. Kenya Electricity Generating Company Ltd (KenGen) owns major operating geothermal plants in Kenya, their implementation of social sustainability policies has improved local communities’ quality of life. Major improvements came from infrastructure construction. With enhanced transportation and telecommunication, the Maasai community gained access to markets and other facilities (Mariita, 2002). Also, many Maasai families appreciated the benefits from the provision of clean water, schools and shops. In terms of economic impacts, the establishment of the geothermal plant provided job opportunities (Mariita, 2002).

On the big scale, the development of geothermal energy contributed to the growth of the economy and improvement of living conditions. Energy sector contributes directly to the economy through job provision and tax revenue (Voser, 2012). Benefits also occur when workers spend their incomes in local economy which creates economic activities in other sectors such as retail, leisure and entertainment (Akella, et al., 2009). Also, it may relieve the dependence on oil and gas for energy generation, especially Kenya relies entirely on imported oil & gas. From 2008 to 2015, through the establishment of Rural Electrification Programme (REP), 703,190 costumers were connected (Republic of Kenya, Ministry of energy and petroleum , 2016). Geothermal power stations are connected to the national electricity transmission grid and contribute to REP through provision of electricity to nearby rural communities. Having access to electricity improved their living conditions through better health condition, empowerment of education, modern farming and fishing and employment creation (Ayieko, 2011).

Despite the benefits, geothermal projects posed various challenges to the area. Mariita, (2002) reported the commission of Olkaria I power plant on indigenous people’s land reduced grazing land to an extent that was too small to sustain. In addition, local communities were evicted without compensation. The situation preserved when Olkaria IV power station was commissioned. The Maasai was resettled in areas distant to their source of livelihood and census irregularities caused incorrect settlement allocations. Concerns also came from the unreliability of the water supply, poor quality housing and threats from mudslide (Schade, 2017). In addition, none of the Maasai homesteads have electricity access, despite the presence of geothermal plants (Mariita, 2002).

Environmental impact:

The rift-valley is very environmental sensitive, it suffers from low rainfall, loose soils and high ground slope. Therefore, to reduce environmental damages, proper management and preparation for road construction, drill-site and effluent disposal are required. Due to insufficient number of KenGen environmental staff on environmental assessment and monitoring programmes, environmental issues such as soil erosion, noise and gaseous pollution are associated with the Olkaria I power station (Mariita, 2002). The primary cause of soil erosion is the surface disposal of wastewater from power plants to arid rift valley floor where the loose volcanic soils are highly susceptible to water erosion (Mwakio, 1996). The recorded noise level at Olkaria ranges from 104 dB(A) within 15m of the drilling wells to about 60 dB(A) in the open area within the power station (Knight, 1994). Therefore, operators are required to wear protective equipment and work in shifts. Because of the long distance between local communities and geothermal plants, the impact of noise is minimum outside the station (Mariita, 2002). Although the greenhouse emission from geothermal energy exploitation is much less than that released from fossil fuels, research is required to quantify the impact of greenhouse gases on micro climate and animal and plant growth (Mwakio, 1996). Analysis of geothermal emission of H2S at Olkaria shows that it is below the World Health Organization harmful levels (Knight, 1994). However, Maranr, (1994) show a presence of high concentration of H2S near generation buildings. In 2002, the Maasai reported they were suffering from respiratory diseases, eye problems, fertility problems including miscarriages and birth defects (Schade, 2017). As a major health threat, more studies on H2S and measures to reduced H2S emission are required.

At the national level, the development of geothermal energy promoted environmental sustainability by lowering the dependency on fossil fuels and biomass based energy. Geothermal power plants generate less CO2 emission than conventional energy sources (Fig. 4) and does not involve discharges of liquid containing poisonous substances (Akella, et al., 2009). Like many developing countries, biomass is the major energy source in Kenya (74.6%), especially to the domestics and residential sectors (Kiplagat, et al., 2011). 93% of biomass come from fuelwood, which posed a big threat on Kenya’s remaining forests. Through REP and replacing biomass with energy from geothermal and other renewable resources, deforestation and biodiversity loss due to over-exploitation of forests have been limited (Practical Action, Eastern Africa Office , 2010).

Concusion

After examining various research on the impacts of geothermal development in Kenya, I came to conclude that geothermal energy exploitation has contributed to the growth of economy and improvement of the quality of life. It will be increasingly crucial for the Kenya to achieve the Vision 2030.

Rural communities benefit from improved infrastructure in region where geothermal power stations situate. Such improvements include access to clean water, education and transportation. However, issues related to resettlement policy (such as poor quality housings and reduced grazing land) need to be resolved. On the national scale, geothermal contribute significantly to Kenya’s electricity supply, as well as job provision and tax revenue. Although, geothermal power stations produce less air and water pollution, the environmental benefits are less significant as biomass remains the major energy sources. In addition, energy companies need to reduce soil erosion and impacts from H2S emission.

The Kenya Vision 2030 incorporates further geothermal energy development projects in the Rift Valley, that will ensure a more sustainable socio-economic development. Currently, geothermal energy production is restricted in Olkaria. Commissions of geothermal power station in other areas such as Baringo low land provide affordable energy to local communities for health purposes (such as sterilization and immunization), education purposes (such as improved school facilities and access to information) and economic activities (such as access to markets and other facilities). In addition, it may reduce the usage of biomass therefore limiting greenhouse gas emission and deforestation.

FOOTNOTES

This is a short summary of my original report. If you are interested in the detailed mechanism, please get in touch

References

-

Abdullaha, S. & Markandya, A., 2012. Rural electrification programmes in Kenya: Policy conclusion from a valuation study. Energy for Sustainable Development , 16(1), pp. 103-110.

-

Akella, A. K., Sharma, M. P. & Saini, R. P., 2009. Social, economical and environmental impacts of renewable energy systems. Renewable Energy, 34(2), pp. 390-396.

-

Armannsso, H., Fridriksson, T. & Kristjansson, B. R., 2005. CO2 emissions from geothermal power plants and natural geothermal activity in Iceland. Geothermics, June, 34(3), pp. 286-296.

-

Ayieko, Z. O., 2011. Rural electrification programme in Kenya, s.l.: World Bank .

-

Dawson, J. B., 2008. The Gregory rift valley and Neogene-recent volcanoes of northern Tanzania. London: Geological Society of London.

- Deloitte, 2016. Kenya Economic Outlook 2016 The Story Behind the Numbers , s.l.: Deloitte.

-

Dickson, M. H. & Fanelli, M., 2003. Geothermal energy: utilization and technology. France : United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO).

-

Edwards, L. M., Chilingar, G. V., Rieke III, H. H. & Fertl, W. H., 1982. Handbook of Geothermal Energy , Houston : Gulf Publishing Company Book Division .

-

Entingh, D. J., Easwaran, E. & McLarry, L., 1994. Small geothermal electric systems for remote powering, Wahington D.C.: US Department of Energy, Geothermal Division.

-

Gudmundsson, J. S., 1988. The elements of direct uses. Geothermics, Volume 17, pp. 119-136.

-

KenGen , 2017. Integrated annual report & financial statements for the year ended 30 june 2017, s.l.: Kenya Electricity Generating Company Limited.

-

KenGen, 2016. Integrated annual report & financial statements for the year ended 30 june 2016, s.l.:

-

Kenya Vision 2030, n.d. Sessional paper No…..of 2012 On Kenya Vision 2030, Nairobi: Office of the Prime Minister Ministry of state for Planning, National Development and Vision 2030.

-

Kiplagat, J. K., Wang, R. Z. & Li, T. X., 2011. Renewable energy in Kenya: Resource potential and status of exploitation. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, August, 15(6), pp. 2960-2973.

-

Knight, S., 1994. Environmental Assessment Draft Report on North East Olkaria Power Development Project, Nairobi: Kenya Power Company Ltd. .

-

Marani, . M., 1995. Spatial-temporal variations of hydrogen sulphide concentration levels around the Olkaria Geothermal Power Plant, s.l.: Moi University, Kenya.

-

Mariita, N. O., 2002. The impact of large-scale renewable energy development on the poor: environmental and socio-economic impact of a geothermal power plant on a poor rural community in Kenya. Energy Policy, September, 30(11-12), pp. 1119-1128.

-

Moksnes, N., Korkovelos, A., Mentis, D. & Howells, M., 2017. Electrification pathways for Kenya–linking spatial electrification analysis and medium to long term energy planning. Environmental Research Letters, 11 September .12(9).

-

Mwakio, T. P., 1996. Geothermal energy research in Kenya: a review. Journal of African Earth Sciences, 23(4), pp. 565-575.

-

Ogola, P. F. A., Davidsdottir, B. & Fridleifsson, I. B., 2011. Lighting villages at the end of the line with geothermal energy in eastern Baringo lowlands, Kenya – Steps towards reaching the millennium development goals (MDGs). Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 15(8), pp. 4067-4079.

-

Omenda, P. A., 2008. Status of geothermal exploration in kenya and future plans for its development, s.l.: United Nation University Geothermal Training programme .

-

Practical Action, Eastern Africa Office , 2010 . Biomass energy use in kenya, Nairobi: Practical Action Consulting .

-

Republic of Kenya, Ministry of energy and petroleum , 2016. Kenya’s investment prospects, s.l.: sustainable energy for all .

-

Riaroh, D. & Okoth, W., 1994. The geothermal fields of the Kenya rift. Tectonophysics, Volume 236, pp. 117-130.

-

Schade, J., 2017. EU accountability for the due diligence failures of the European Investment Bank: climate finance and involuntary resettlement in Olkaria, Kenya. Human Rights and the Environment, Volume 8, p. 72–97.

-

Shortall, R., Davidsdottir, B. & Axelsson, G., 2015. A sustainability assessment framework for geothermal energy projects: Development in Iceland, New Zealand and Kenya. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, October, Volume 50, pp. 372-407.

-

The Word Bank, 2014. Access to electricity (% of population). [Online] Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EG.ELC.ACCS.ZS?end=2014&locations=KE&start=1990&view=chart&year=1992 [Accessed 11 February 2018].

-

Voser, P., 2012. Energy for Economic Growth, s.l.: Energy Vision Update .

-

Wheildon , J. et al., 1994. Heat flow in the Kenya rift zone. Tectonophysics, 30 September, 236(1-4), pp. 131-149.

- World Energy Council, 2016. World Energy Resources Geothermal 2016, London: World Energy Council.